Agile Software Architecture: From Idea to System – but Never Quite as Planned

An Article by Stefan Toth

Holidays are great. I had been looking forward to it for weeks and spent days planning the route and booking hotels. Now I’m standing in front of our house with my family, the taxi isn’t coming, and my five-year-old son is whining about the heat and how boring it is to wait.

When the taxi finally arrives, the child seat we ordered is missing, but somehow we make it to the train station. We arrive at our holiday destination much too late, only to find out on site that the accommodation is not usable due to last-minute renovations. We quickly look for a hotel and are no longer quite so sure how great holidays really are…

Of course, holidays are great. But you sometimes have to admit: they’re not always as smooth and relaxing as expected. With enough travel experience, you develop a certain calmness and learn how to deal with surprises. Not everything can be controlled – and comedy is, after all, just drama plus time.

Software architecture is also great. I would argue that holidays and architectures have a lot in common. Architecture plans rarely survive the first encounter with reality. What we end up building is never what we initially drew up on the whiteboard. That’s not an exception – it’s the normal mode of operation for designing software.

Modern software development is fast, distributed, and characterized by constant change. New frameworks, tools, platforms, and paradigms emerge all the time, decisions have unexpected side effects, and technologies reveal unforeseen problems. Couldn’t we have done it right from the start? Shouldn’t we have figured that out beforehand?

Actually: No. With some development experience, you develop a certain calmness and learn how to deal with surprises. Not everything can be controlled – and comedy is, after all, just drama plus time.

Architecture and Agility as Ideal Partners

Modern definitions of software architecture have one thing in common: they describe the discipline as being concerned with the core elements of a system – the ones that are difficult to change later on. Martin Fowler puts it this way:

“To me, the term architecture conveys a notion of the core elements of the system, the pieces that are difficult to change. A foundation on which the rest must be built.”

In the 1980s, these foundational, hard-to-change decisions were mostly structural in nature. How should our system be broken down into components? What interfaces should it have? How should we store data?

In the 1990s, more programming languages, networking, and virtualization of systems became increasingly important choices. IBM mainframes and Unix workstations had previously been the only real options. Now, new server technologies emerged. In 1995 alone, Windows NT, the Apache HTTP Server, and programming languages like Java, PHP, JavaScript, Ruby, and Delphi saw the light of day. These also brought new patterns and implementation strategies. With the rise of the internet, software users became more numerous and geographically dispersed. Software had to be not only maintainable, but also secure, reliable, usable, and scalable – all under more complex technical conditions.

Today, the number of programming frameworks, environments, and tools is immense. In the field of AI alone, new frameworks appear daily. It’s difficult to maintain an overview of all relevant technologies – let alone be an expert in all of them.

As a result people with different areas of expertise must collaborate dynamically to create good software and design tasks have become increasingly interwoven. Since the Agile Manifesto in 2000, agility has supported the necessary networking of roles and feedback-driven work on software. It has become the ideal partner for the modern discipline of software architecture.

Figure 1: The Manifesto of Agile Architecture Work [1]

Figure 1 shows the “Manifesto” for modern architecture work, with its four central value pairs: continuous improvement, goal-oriented design, collaboration, and widely distributed responsibility are identified as most important. This is based in part on the work of David J. Snowden [2]. In his writings on handling complex problems, he recommends an approach optimized for experimentation: probe – sense – respond. These broadly defined theoretical foundations transfer well to software architecture. The manifesto illustrates core ideas and promotes the tight integration of software design and implementation work.

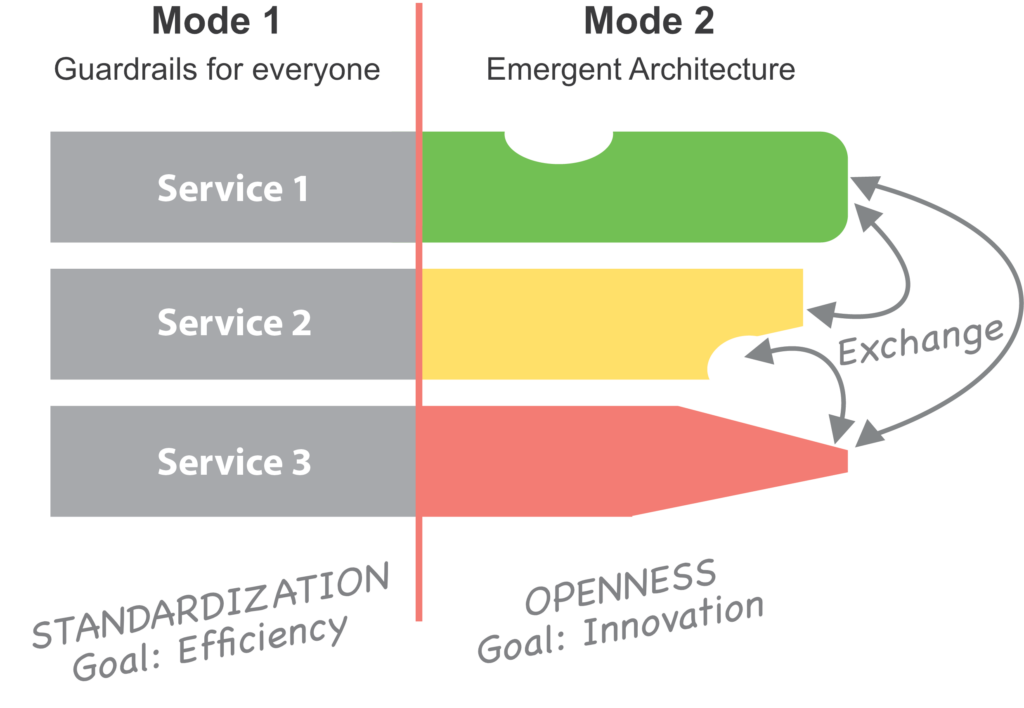

The Two Modes of Agile Architecture Work

Anyone practicing software architecture in an agile environment ideally moves between two working modes.

Mode 1: Guardrails provide orientation

Part of architecture work is to establish guardrails to steer software development over time into a desired direction. These guardrails could be fundamental decisions about programming languages, infrastructure, data storage, or security models, such as:

- Technical principles: “All external calls must be encrypted.”

- Non-functional requirements: “Latency must always remain under 200 ms.”

- Reference implementations: “Always use these Docker base images.”

- Automated checks: “In the CI/CD pipeline, dependencies on third-party libraries are verified.”

Guardrails prevent chaos and are meant to provide teams with orientation, reduce the cognitive load during implementation, and create space for focused creativity.

If architecture work remained solely in this mode, it would soon seem traditional and eventually be perceived as rigid or obstructive. That’s why in agile contexts, guardrails must be continually challenged and evolved. They should be lightweight and never bind resources excessively.

Mode 2: Architecture evolves continuously

If a service truly scales, whether an implementation idea is viable, or whether a change holds up over time is hard to tell at design time. Dependable Feedback is more common during implementation or after deployment. Instead of detailed planning, we need experience and evidence. In this second mode, architecture is seen as a hypothesis, that needs to be (in)validated:

- through small experiments (spikes),

- through telemetry and log analysis,

- through feature flags or shadow deployments,

- through conscious communication of insights (e.g., in communities or ADRs).

This kind of architecture work thrives on observation, experimentation, and learning. The best ideas don’t come from meeting rooms – they arise while debugging, reflecting on system behavior, or grappling with difficult problems.

Working on real problems gradually creates new guardrails, softens existing ones, or leads to an architectural practice that gently guides teams — more effectively than hard rules do.

To enable this bottom-up architecture approach, teams need a solid understanding of goals and context, enough opportunities for cross-team exchange, and fine-grained feedback mechanisms on a technical level. This part of architecture work has been growing steadily in importance since 2000. Most practices labeled “agile architecture” aim to make this mode effective and practical.

Figure 2: The Two Modes of Modern Architectural Work

Practices to interweave the two modes

Successfully establishing emergent architectural practices (mode 2) as a complement to classical guardrails (mode 1) requires specific techniques. If you are interested, take a look at [1] where practices for these modes and their synergy are discussed in detail. Here a few concepts to convey the core ideas:

- Continuous Architecture: Architecture is understood as a continuous, measurable series of experiments rather than a one-time design activity. Exploratory spikes with feedback loops test new ideas realistically.

- Quality Goals as Drivers: Quality goals are central to architecture and visible to all stakeholders. They also effect team backlogs.

- Feedback First: Health checks and telemetry are central, and architectural rules are continuously verified through them.

- Soft Standards, Hard Limits: Not everything is mandated. There are binding principles and best practices alongside freedom for innovation.

- Lightweight Reviews and Decision Formats: Low-barrier formats like peer reviews, architecture office hours, or decision-making workshops foster reflection without bureaucracy.

- Organizational-Architectural Alignment: Good architecture also requires organizational support. For example, team boundaries should align with domain boundaries, and team responsibilities should match the expected level of innovation.

Sources

[1] Toth, Stefan: “Vorgehensmuster für Softwarearchitektur. Kombinierbare Praktiken in Zeiten von Agile und Lean”; Carl Hanser Verlag, 2025

[2] Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E.: “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making”; in: Harvard Business Review, 2007

About the Author

Stefan Toth is the founder of embarc GmbH and author of numerous articles and the books “Vorgehensmuster für Softwarearchitektur” and “Software-Systeme reviewen”. As a consultant, he supports startups, SMEs, and large corporations in realigning their organizations, methods, and technologies.