How Artificial Intelligence Is Changing the Role of Software Architects

How AI Systems Expand the Software Architect’s Toolbox – and What This Means in Practice | An Article by Sönke Magnussen

Architecture Becomes Intelligent – and More Complex

The rapid development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not only changing our understanding of what software can do; it is also profoundly reshaping the self-image of those who design it: software architects. Where architectural work once primarily involved designing technical structures based on classical software components and interfaces, today it increasingly means integrating components built on complex, barely interpretable domain models. These models are trained from data using machine learning and must be continuously adapted and retrained over time.

Architecting such systems introduces new challenges – not only on a technical level, but also methodologically.

The Classical Toolbox Is Expanding

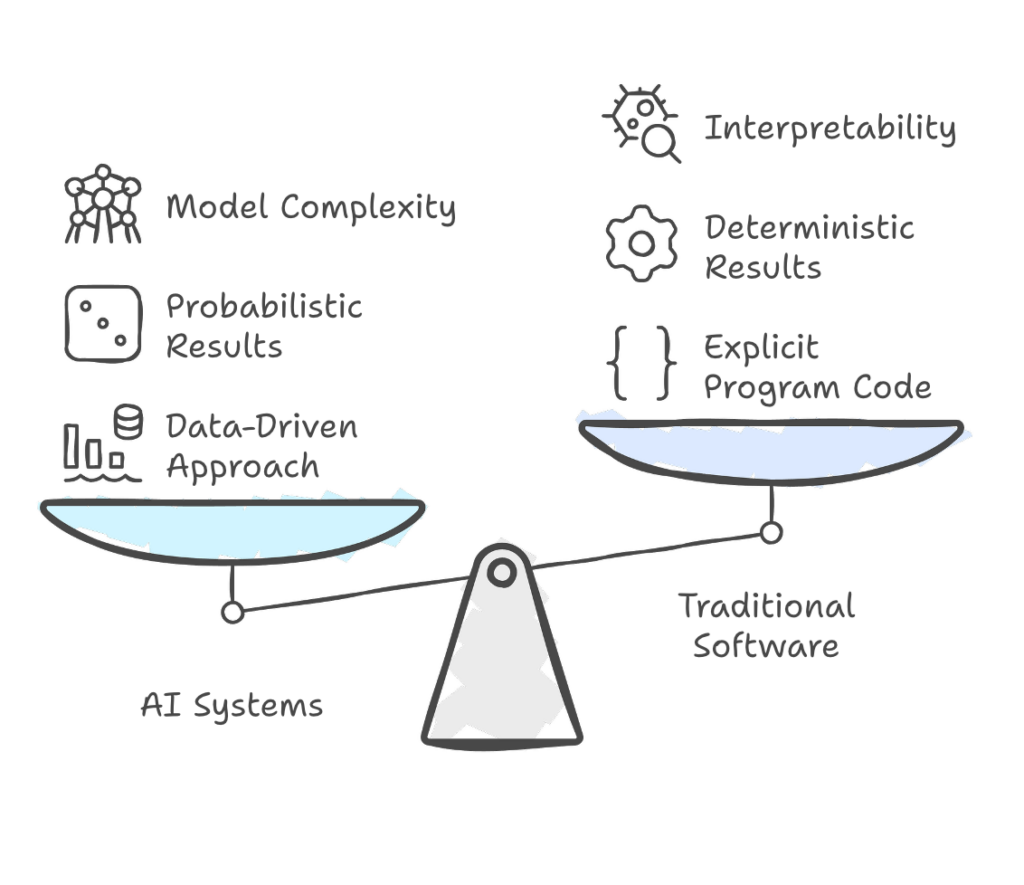

With the introduction of AI into the software development toolbox, the traditional design process gains a crucial new dimension. AI-based components no longer follow strictly deterministic logic that can be fully understood through source code. Instead, they behave in a data-driven, dynamic, and in some cases opaque manner.

This expanded design space opens up fascinating possibilities: IT systems become more flexible, adaptive, and in many cases significantly more powerful than purely rule-based predecessors. At the same time, however, the responsibility of software architects grows. These systems behave probabilistically, and the uncertainty they introduce must be addressed by other components of the system as well as by the user interface. Designing such systems in a comprehensible and secure way becomes a central architectural task.

Hybrid Systems Require New Ways of Thinking

It is becoming increasingly clear that AI is no longer a special case or an add-on, but an integral part of modern system architectures. Established architectural approaches such as layered architectures, microservices, or domain-driven design are not rendered obsolete – instead, they take on new distributions of responsibility through the targeted use of AI.

A new class of hybrid systems is emerging, in which algorithmic components interact with trained models. Determining where AI should be located – whether as a microservice, an embedded module, or an external service (Model as a Service, MaaS) – is a core architectural decision. Equally important are questions around data integration, ownership, responsibility, and accountability.

Architecture Work Becomes More Dynamic and Data-Driven

What matters most is not the size or complexity of an AI component, but its functional role within the overall system. In many cases, even a simple classification model or heuristic anomaly detection can deliver substantial value.

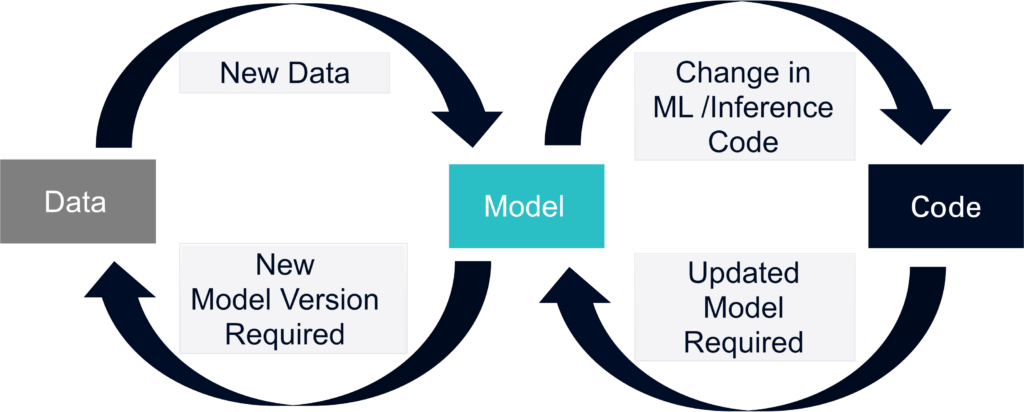

The key competence for modern software architects lies in integrating these components purposefully into existing architectures. This introduces questions that were rarely central to traditional architecture work: How can training data be versioned? How are model updates rolled out into production? How can model performance be ensured under changing conditions over time?

New Roles and Areas of Responsibility

As a result, the role of software architects is evolving. They are no longer just designers of technical structures, but increasingly act as interfaces between data science, development, operations, and governance. Architects must understand both the potential and the limitations of AI – and be able to translate this understanding into concrete system designs.

Functionality alone is no longer sufficient; trust in the system becomes equally important. Many AI components make decisions that cannot be fully explained in detail and do not always produce correct results. This makes it essential to incorporate architectural mechanisms for transparency, monitoring, logging, and safeguards that ensure robust and trustworthy system operation.

Operations Become Part of the Architecture

In addition, an operational dimension gains importance – one that has traditionally received little attention in classical software architecture. While conventional systems evolve mainly through code changes, AI systems often change through new data used to train new model versions.

Operating learning systems therefore requires new structures, such as continuous training pipelines, performance monitoring, and model validation. Concepts like MLOps introduce new areas of responsibility with both technical and organizational implications. Software architects are challenged to incorporate these processes early in their architectural designs to enable scalable and maintainable operating models later on.

AI as a Deliberate Decision – Not an End in Itself

Another critical question is when the use of AI actually makes sense. Not every problem requires a neural network or a language model. Instead, AI should be considered deliberately in situations where rule-based approaches reach their limits, large amounts of data are available, or decision logic changes frequently.

Being able to make this assessment in a well-founded way is yet another emerging competence for software architects – and a domain in which they can significantly influence strategic decisions.

Architecture as a Place of Responsibility

Finally, integrating AI raises ethical and regulatory questions that directly affect architectural decisions. Issues such as fairness, explainability, data sovereignty, and energy efficiency are no longer purely political debates. They influence system design, technology choices, and operational architectures.

Architecture thus becomes a place where societal responsibility is exercised.

Conclusion: Architectural Perspective Determines the Success of AI

Artificial Intelligence is not merely a technological innovation – it represents a cultural shift in how we think about, build, and operate software. For software architects, this means a dual movement: embracing new tools and methods while actively shaping their role and responsibility within these new systems.

This transformation requires more than technical expertise. It calls for design courage, strong communication skills, and a deep understanding of how technology affects organizations. The working world of software architects will continue to evolve. Those who see AI not as a foreign element but as a design tool will be able to create systems that are not only powerful, but also sustainable – and that keep people at the center for whom these systems are ultimately built.

About the Author

Dr. Sönke Magnussen is a software architect with many years of experience in transforming complex IT systems and designing modern architectures using DDD, cloud, and DevOps. His focus lies on integrating AI – from classification models to GenAI chatbots. He deepened his AI expertise through, among other things, an AI Nanodegree (Udacity) and by co-developing the iSAQB module SWArch4AI. As a trainer and consultant, he combines deep technical expertise with a strategic perspective on software architecture.