The Profession of “Software Architecture”

An Article by Dr. Gernot Starke

Warning: This article contains opinions. The author still enjoys software architecture after more than 20 years of professional experience.

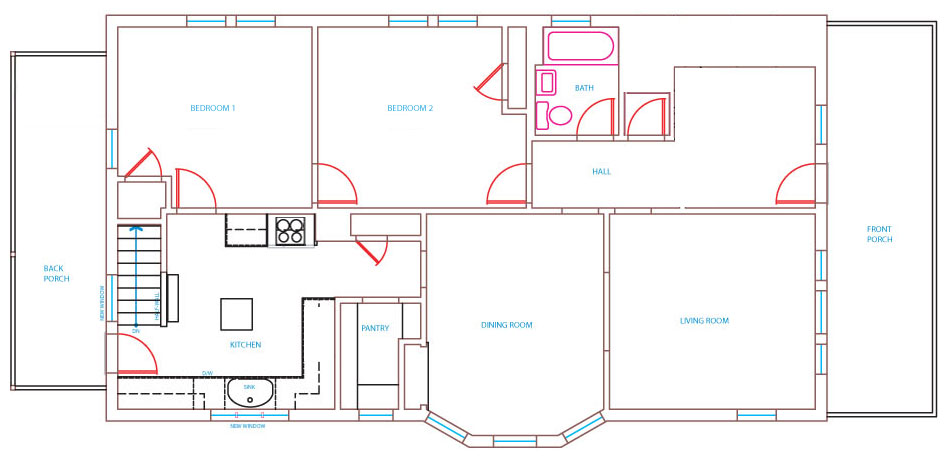

Before we can clarify the role of software architects in IT projects, we need to understand the term software architecture itself. The word architecture is borrowed from the construction industry, and it is worth looking at analogies from that domain:

- Identifying the essential requirements, for example together with future users, clients, and authorities

- Floor plan: which rooms exist, and how are they structurally connected?

- Building materials: which materials are used to construct which parts of the building?

- Design of the external shape, façade, aesthetics, and urban planning constraints

- Connection to surrounding infrastructure: roads, water, electricity, internet

- Consideration of requirements such as structural stability, soil conditions, fire protection, etc.

- Accompanying the construction process: clarifying open questions as they arise

You can find many more details on these fundamentals in [1].

Figure 1: Example floor plan

“Software Architecture” – What Does It Mean?

Just like with buildings, we need to understand the exact requirements for the system’s functionality, its quality attributes (e.g., throughput, availability, performance, security), and its expected behavior in productive operation. Are we allowed to update the system during operation – and if so, how?

With the “floor plan,” we decide on the structural composition of systems made up of components such as packages, namespaces, modules, and services, including their interfaces. These are the familiar “boxes and arrows” diagrams – still missing important information about our “building materials”: programming languages, libraries, and everything commonly summarized as the tech stack.

The connection to neighboring systems – referred to as external interfaces (system context) – is equally important. This is where major risks often lurk, only to grow into serious problems during production operation [2].

With these foundations in place, we can now better classify the role and professional profile of software architects.

What Do I Have to Do?

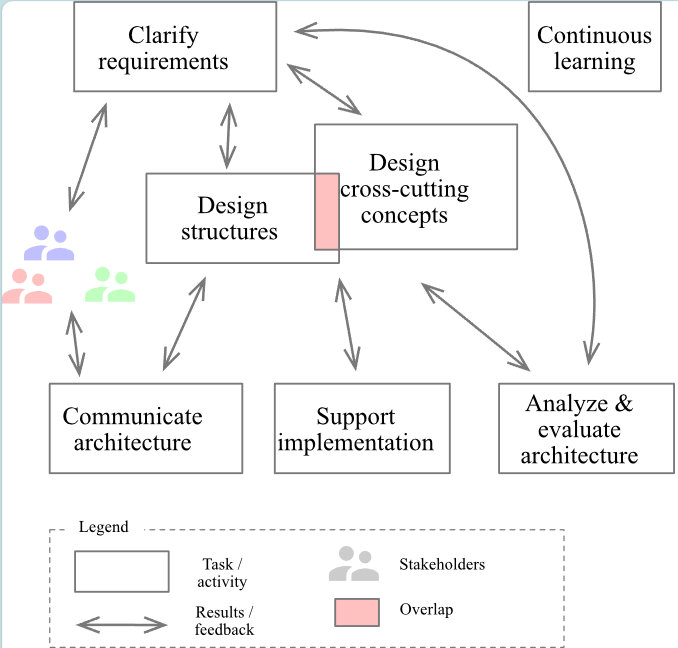

Professional roles are best described by the tasks and activities they involve. For software architecture, Figure 2 shows a widely accepted proposal – compatible with the views of iSAQB® [3] and arc42 [4]. Continuous feedback forms an essential foundation for these tasks. Improve the architecture based on feedback from relevant stakeholders and constantly question both structural (“floor plan”) and technical decisions.

Figure 2: Tasks in software architecture

Figure 2 shows the essential design and decision-making tasks. These are based on the (hopefully clarified) requirements (top left). You communicate the decisions to relevant stakeholders (bottom left) by explaining, justifying, motivating, and documenting them.

The task accompany implementation is performed continuously and collaboratively with the development team. Both sides should ensure that the implementation conforms to the intended architecture. You can find more details on these tasks in [7].

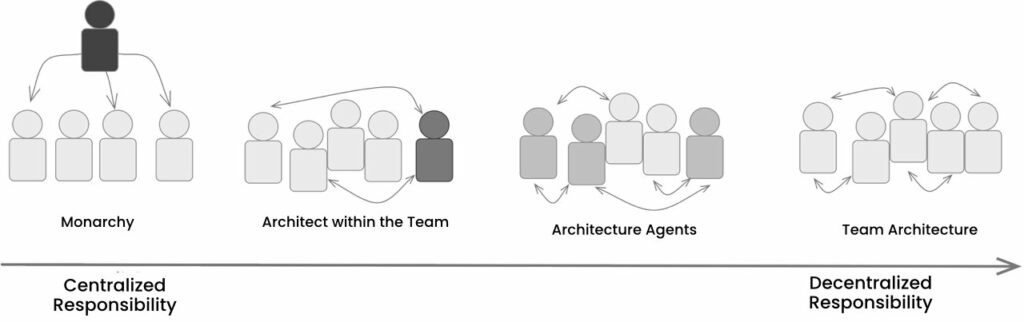

I will not address here the difficult question of whether and how these tasks should be distributed across a team or assigned to a single person. As a consolation, Figure 3 shows a spectrum of possible approaches (originally described by Gregor Hohpe in [6]).

Figure 3: Who takes on the tasks?

How Does This Work?

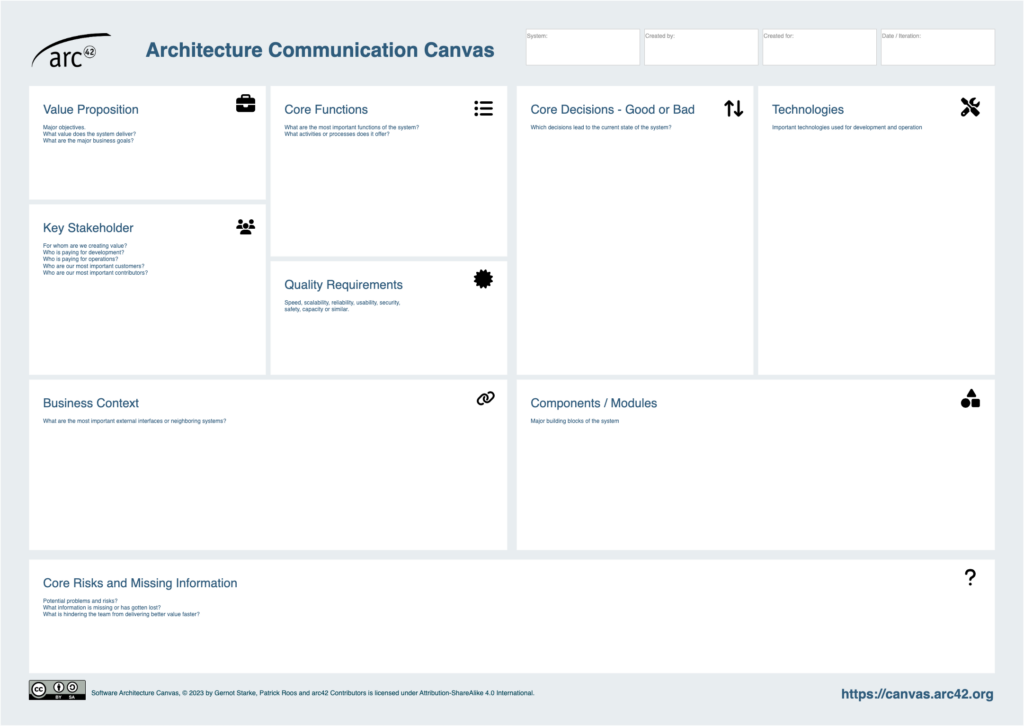

Start by documenting the essential aspects and decisions of your own architecture in a one-pager (see [5] and Figure 2). This makes a substantial portion of the relevant foundations and decisions explicit and enables you to gather feedback from stakeholders.

Figure 4: Architecture Communication Canvas

How you choose an appropriate “floor plan” and suitable implementation and operational technologies for your specific requirements would go beyond the scope of this article. For guidance on structural design, see the article on the Domain-Driven Design (DDD) module. In addition, there are many fundamental principles (such as loose coupling, high cohesion, information hiding, modularity, etc.) and a wide range of patterns as supporting tools.

Ultimately, architectural decisions are always situational – based on the specific context. That sounds difficult, and in my experience, it is difficult. Which brings us to the final question: how can you learn this?

How Do I Get There?

In my experience, you should spend several years programming and actively working in software development. This gives you the necessary “instinct” to recognize and navigate uncertainties and risks in design and architecture.

In addition, strong communication skills are essential – across many different stakeholder groups. The better you are at adapting to the languages and goals of these people, the better your architectural decisions will be.

So: practice, practice, practice – and always seek feedback.

Conclusion

In my view, the role of the software architect carries responsibility for the successful realization of requirements. This involves making a number of fundamental decisions, either alone or together with a team.

You can creatively incorporate your own experience and thereby positively influence IT projects and products. You must communicate and sometimes argue for decisions – even in the face of resistance. For motivated developers, software architecture often means greater responsibility and broader influence.

May the power of good decisions and well-formulated justifications be with you!

Links and References

- [1] Gernot Starke, Fundamentals of Software Architecture

https://www.innoq.com/de/articles/2023/07/architektur-teil‑1/ - [2] Gernot Starke, What Is Software Architecture?

https://www.innoq.com/de/articles/2023/09/grundlagen-der-softwarearchitektur-teil‑2/ - [3] iSAQB, Foundation Level Curriculum for Software Architecture

https://public.isaqb.org - [4] arc42, The Open-Source Template for Communicating Software Architectures

https://arc42.org - [5] Architecture Communication Canvas (Open Source)

https://canvas.arc42.org - [6] Gregor Hohpe, Architecture Elevator: Would You Like Architects with Your Architecture?

https://architectelevator.com/architecture/organizing-architecture/ - [7] Gernot Starke, Tasks in Software Architecture

https://www.innoq.com/de/articles/2023/10/grundlagen-der-softwarearchitektur-teil‑3/

About the Author

Dr. Gernot Starke is an INNOQ Fellow, co-founder of arc42, aim42, and iSAQB®, speaker, coach, and consultant. He has more than 20 years of hands-on experience in software architecture across various domains, including logistics, telecommunications, finance, engineering, automotive, and retail.