Domain-Driven Design: Avoiding Misunderstandings to Protect Your Investment

An Article by Carola Lilienthal

Software development is a process prone to misunderstandings: future users speak their own business language, while the development team comes from a technical world and is tasked with creating something that doesn’t yet exist – innovative and state-of-the-art. So failure is definitely an option!

“It’s developers’ (mis)understanding,

not domain experts’ knowledge,

that gets released in production.”

– Alberto Brandolini, creator of Event Storming

With this quote, Brandolini hits the nail on the head: understanding Domain-Driven Design (DDD) is absolutely essential for everyone involved in the software development process. In software development, we must succeed in deeply understanding the domain and transferring that knowledge into the software.

Only then can we build systems that fully match the tasks domain experts expect the software to fulfill. On one hand, domain-driven software improves and accelerates business processes. On the other, we can continue evolving the system in line with the domain over many years, because domains are typically more stable than the technologies we use.

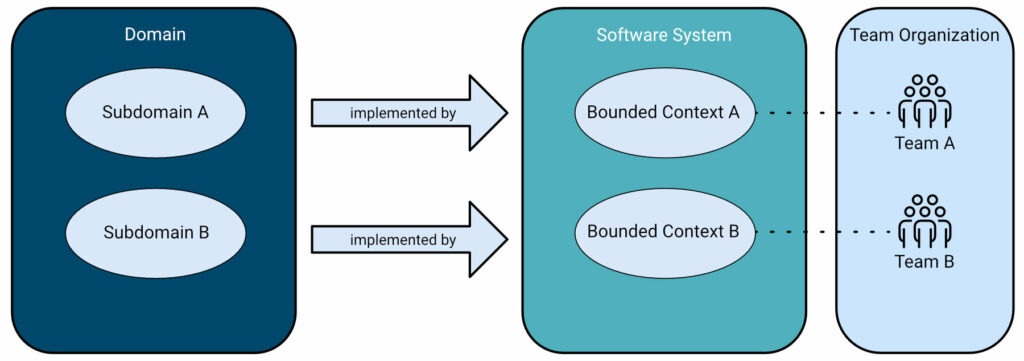

DDD is a methodology that puts this domain-centric approach front and center (see Lilienthal 2023). Together with domain experts, the development team gains an understanding of the domain’s processes and language in an agile way. The techniques used to gather requirements are summarized in DDD under the term “Collaborative Modelling.” The knowledge gained is transferred into a Context Map (Fig. 1), Bounded Contexts, the Ubiquitous Language, domain models, and ultimately into source code. Let’s take a closer look at these steps.

Figure 1: Relationship between domain, software system, and team structure

Collaborative Modelling and Strategic Design

Collaborative Modelling is used at various “altitudes” throughout the project. We begin with the big picture – a high-level view of the domain – and analyze cross-cutting processes. Based on this analysis, we start with DDD’s Strategic Design. This involves identifying subdomains within the main domain and assessing their importance (Core, Supporting, Generic Subdomains). This evaluation helps the development team and management decide where to invest resources and where buying third-party software might be more effective.

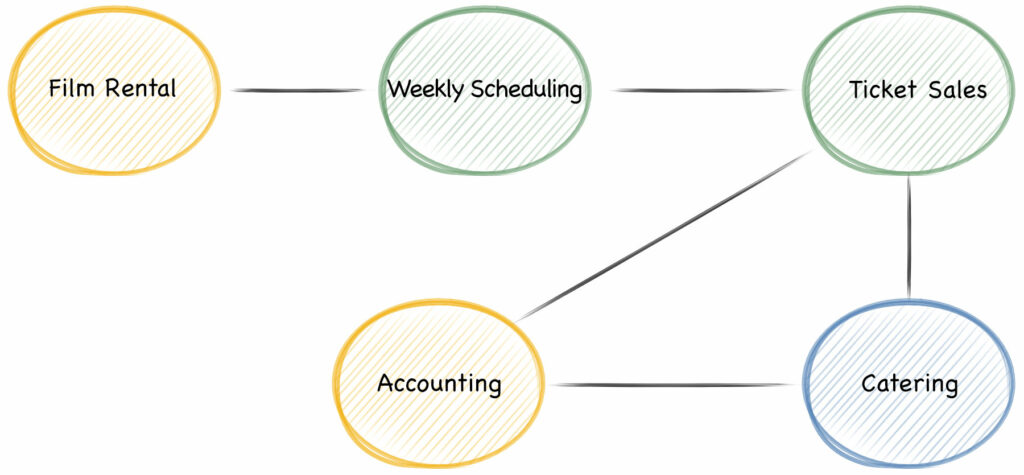

Figure 2: Example of a Context Map for a cinema domain

To gain an overall view of the system architecture, we then create a so-called Context Map that shows subdomains and their relationships in the form of Bounded Contexts (see Fig. 2). The Context Map defines the structure of the software, using Bounded Contexts as domain-driven modules and identifying their interfaces through Context Mapping. This gives us a domain-driven architecture that can also guide how we structure our teams (see Conway 1968).

Ubiquitous Language and Tactical Design

Each Bounded Context has its own Ubiquitous Language – a shared domain vocabulary – and its own domain model, which is then translated into source code.

A DDD-based system consists of several modules, each with a domain model tailored to the specific Bounded Context. This allows each model to precisely address its subdomain.

For creating these domain models, DDD provides guidelines through Tactical Design. It defines five types of classes, each implemented according to a specific pattern and connected to one another: Entity, Domain Value, Service, Repository, and Factory. One technique that helps with modeling these classes is Example Mapping, derived from Behavior-Driven Development (BDD; see North 2006). This approach helps define scenarios for domain-driven acceptance testing and model class interfaces and interactions accordingly.

Conclusion and Outlook

Like most living methodologies, DDD is constantly evolving. Currently, the DDD community is actively discussing concepts like Team Topologies (see Skelton 2025) and Wardley Maps (see Wardley 2017). Team Topologies has broadened our view of team organization beyond just Stream-Aligned Teams, which implement a Bounded Context. It invites us to also consider Platform Teams, Enabling Teams, and teams focused on Complicated Subsystems.

Wardley Maps help us make strategic decisions for the evolution of software solutions visible and understandable to all stakeholders. This enables meaningful discussions with upper management about long-term planning.

When these DDD techniques and concepts are applied throughout the development process – and the domain-driven perspective is maintained during further development – the investment in software will pay off in the long run. DDD helps avoid misunderstandings about the supported domain and leads to systems that truly support their users.

References

- Carola Lilienthal, Henning Schwentner: Domain-Driven Transformation, dpunkt 2023.

- Melvin E. Conway: How Do Committees Invent? In: F. D. Thompson Publications, Inc. (Ed.): Datamation. Vol. 14, No. 5, April 1968, pp. 28–31

- Dan North: Introducing BDD, Better Software Magazine, March 2006

- Simon Wardley: My Basics for Business Strategy, Medium. Hacker Noon, May 2017

- Matthew Skelton, Manuel Pais: Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology for Fast Flow of Value, IT Revolution, 2nd Edition, 2025

About the Author

Dr. Carola Lilienthal is Managing Director of WPS – Workplace Solutions GmbH. On behalf of her clients, she regularly reviews the quality of software architectures. Her experience is captured in the books Sustainable Software Architectures and Domain-Driven Transformation.

Appendix

Ubiquitous Language

DDD encourages everyone involved in a software project to develop a shared domain language – the Ubiquitous Language. This shared language should be based on the business terminology of domain experts, not the technical jargon of developers. The goal is to standardize business terms from the problem space so that they are reflected in the solution space (i.e., the software). DDD recommends using this shared language consistently: in speech, in writing, in diagrams – and in code.

Bounded Context

In a software system, there should be one Bounded Context per subdomain. It comprises part of the source code and has its own database schema. In traditional software architecture, Bounded Contexts would be called modules or components. But from a DDD perspective, the key is that they are defined by domain boundaries.

Wardley Mapping

A Wardley Map is a representation of the landscape in which a company operates. It visualizes a value chain (activities required to meet user needs) and how those activities evolve over time due to competition and demand.

Context Map

The larger the domain and the software, the more domain contexts there will be. To maintain an overview, DDD provides the Context Map – a map of the domain contexts.

Conway’s Law

This principle states that the architecture of a system reflects the communication structure of the organization that created it. In simple terms: the structure of the system mirrors the structure of the teams building it.

Team Topologies

Team Topologies is a concept and framework that provides guidance on organizing and evolving teams within an organization to efficiently build and deliver software. It became widely known through the book by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais published in 2019.

Stream-Aligned Teams

These teams deliver value to customers along the value stream. They are cross-functional, enabling them to deliver significant increments quickly. They have a clear mission and are responsible for the full lifecycle of their products – from development to deployment and operations.